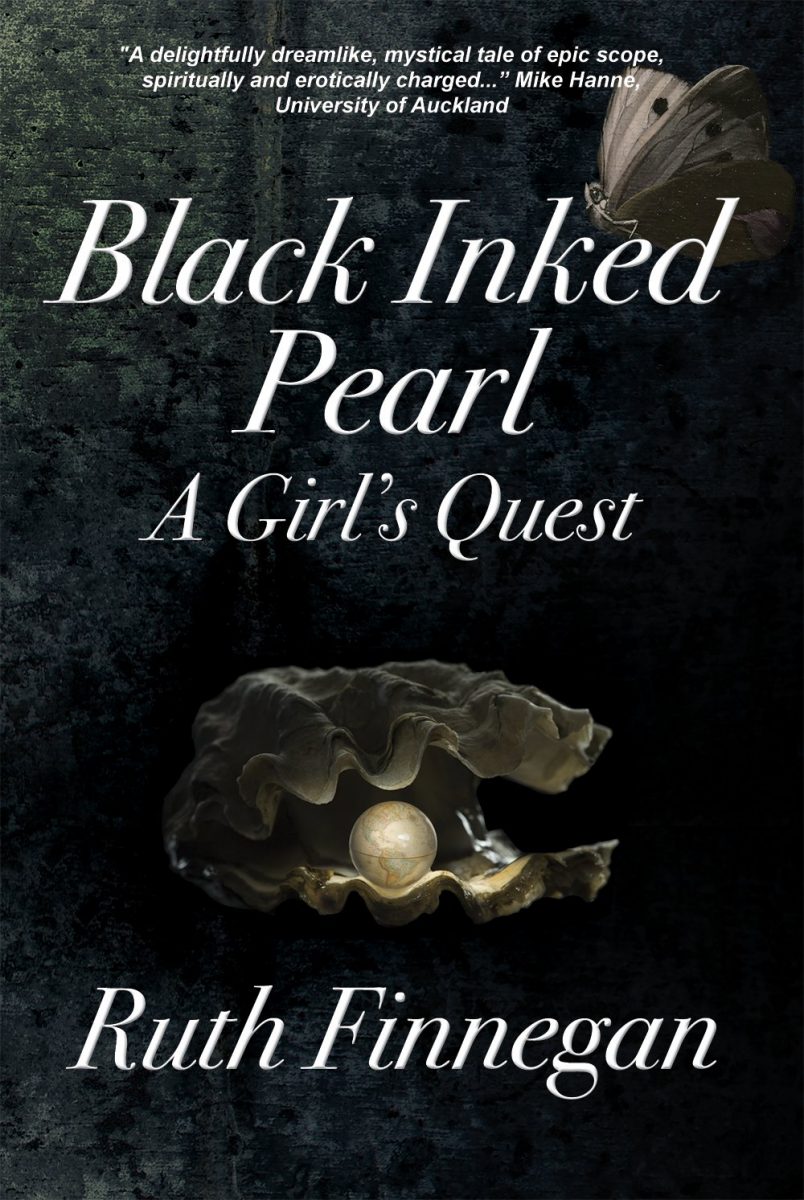

Black Inked Pearl: A Girl’s Quest – Ruth Finnegan | A Review by Sola Adeyemi

Black Inked Pearl: A Girl’s Quest by Ruth Finnegan is an unusual romance novel, the first of that kind I am going to come across in a long while. It is a poetic riddle that expresses the journey of a girl, Kate in search of lost love. The novel is set in the dream world, or rather, is conceived in dreams, with images of this world and another intertwining and interweaving to construct an epic quest reminiscent of the kind found in major world writings. There are echoes from the Greek myths, from Irish folklore, from Christian tenets, from African legends and from that indecipherable existence populated by dream beings. It is indeed a magical book.

Before I had read a few pages, thoughts sprang to my mind: Amos Tutuola is not dead, he is alive in the writing of Ruth Finnegan. There are tales of quest from African myths and folktales, and in the literary works of African writers such as Tutuola, in particular The Palm-Wine Drinkard and his Dead Palm-Wine Tapster in the Deads’ Town (1952), the first African novel in English published outside Africa, where the narrator traces his dead palmwine tapper to the abode of the dead. Or in the Yoruba novels of D. O. Fagunwa where the Quest-motif provides a series of events such as the ones in Black Inked Pearl, where the narrator – in the first instance, Akara-Oogun (in Ogboju Ode Ninu Igbo Irunmole (1939), translated by Wole Soyinka as A Forest of a Thousand Daemons: A Hunter’ Saga (1982) – joins other hunters to brave several vicissitudes in search of peace.

The plot is simple; familiar. The narrative centres on the thoughts of an Irish girl and her lover whose mystery is not quite resolved – or resolved in a magical realist manner – and whom she had rejected in a moment of panic. She traces her recollection from before meeting the lover to expose a life-long quest to finding him. To implant the circumstances of her being and her action, Kate recalls and shares her Irish upbringing in an Irish convent, with all the emotional and academic directions, re-directions and mis-directions that emanated from that. On the banks of an African river, the now very successful professional suddenly recognises a hollowness in her life, the kind that can only be filled by reuniting with a lover whom she had passionately and intensely loved but whom she had rejected nonetheless. Could falling in love have been a result of wanting to revolt against the restrictive Quaker education by a life that is trapped in years of endless indoctrination? I think the answer to that is in the novel.

In any case, Kate begins a quest, an all-consuming quest, to find this mysterious lover whose gaze sets souls on fire and turns young impressionable girls into dreamers of dreams so terrifying and absorbing! She visits all the known physical haunts and the shadowy dream world, including the underworld, to re-cover the lost love – the kingdom of beasts, where the cagy wolf leads her on ‘winged feet… to the great hall to see the heavenly archive’ (p. 108); a trendy London restaurant, an old people’s home, and several other possible rendezvous before heading back to the hazy spaces around the Donegal Sea where it all started. Yet, the lover proves elusive until Kate finally locates the lover trapped in the heavenly spaces of hell that is at once Grecian, Christian, and dreamy. She even becomes ‘translated’ (p. 115) into a golden Garden of Eden which ‘was the traced lacerie of true larch trees, gold into the clouds… and a wondrous beautiful glade with clear sky above, gentle wind blowing, and fragrant soughing song of boughs’ (p. 115). Yes, this dream world has a ‘clear sky’, which is unlike any above the stormy seas off Donegal. She encounters ‘Adam’ and ‘Mr Business Snake’ whose spiels remind one of those scams that could come from anywhere. At a great cost to her life, she saves her lover and dying love. They walk together, hand-in-hand, toward heaven, promising a predictable dénouement to the romantic yarn. However, at the gate separating hell from heaven, the lover escapes first but the Golden Gates clang shut, leaving Kate entrapped by the dusts of hell, enshrouded in her fear and screams and impotence. ‘No man had ever found a path to heaven if the gate was closed… no trumpets on the other side… not purgatory, not hell, not death. Just – nothing… the void. The between no-where’ (p. 241).

But that is not the unhappy ending that the reader by then expects. For the lover now begins his own quest and at last, locates Kate in the dust though, to his anger – fury – and disappointment, and a reverberation of the initial reject, his sacrifice is not recognised and Kate does not thank him. This ageless love is on the wane. And the gates: still shut.

On the way back to heaven, guided by a little beetle – this novel is full of anthropomorphic beings – Kate debates with herself on saving her love, and in the end, in spite of her poor perception of the order of numbers, or of emotions, or of time, and in spite of herself, her lover saves her. Finally, Kate comes to the ultimate realisation – a man (or woman) should not fall in love with a river, for he would have to fall in love with a mountain to understand the river, and he would have to fall in love with the forest to achieve happiness; life – and love – is a riddling riddle. In the end, her quest is not in vain: she finds herself and recognises that she is the unexpected pearl that she thought was buried in the heart of her lover.

Like an enduring dream, the images in this poetic, epic, romantic novel flit through the memory – now vividly clear and memorable; now dull, blunted and fragmented, with moderated emotions and agents of recall. Some clear memories end in the arena of vague meanderings, as the lover feels / webs her way through the warren of reminiscence. At other recollections, the muddled thoughts and disjointed ox-bow lake of ideas suddenly flood over in a dazzling array of lights to reveal a core experience of the relationship between Kate and her lover.

Sprinkled throughout the book are allusions – what the author terms ‘literary allusions’ – to modern and ancient texts, and some original poems, which lend postmodernist assumptions and universalizing propensity to Kate sojourn, emphasizing and questioning relationships, memory and other texts to construct a narrative that threads through a weave of truths, half-truths, faction and surrealistic remembering. There is an resonance of Harold Pinter’s key line in the play Old Times (1971) here: “There are some things one remembers even though they may never have happened. There are things I remember which may never have happened but as I recall them so they take place”. It is this intertextuality, which connects Kate’s ‘life’ to that of the author, as Ruth Finnegan spices Kate’s journey with allusions from Greek texts, the Bible and other historiography that she recollects from her Quaker education in Ireland in the early 21st century, her time at Oxford (Oxenford!) and her passages through Europe, Africa and Australasian regions. At other times, the impression intensely converges on Kate’s mind, with all the undependability of the agent of recall; the dream-like familiarity that scrutinises humanity and that imperfections. At that time, you find ‘understanding’ between the ambiguity of the dream world and the inexplicableness of what we recognise as reality.

This epic love journey is fuelled by love but propelled – wheeled? paddled? encouraged? winged? – by myths and legends as well as those intertextual passages from the Odyssey, Iliad, the Bible, Saint Augustine, Rainer Maria Rilke, Milton, Irish folklore, various modern poems, and by the voice of James Joyce and the nuns from Finnegan’s past. Ogun, the Yoruba god of creativity, war and smithery is summoned to forge a path across ‘The way no-way’ (pp. 248-261). It is a quest that ends in delight, and pain, and joy, and angst, and relief and despair. For, ‘in the beginning was the Word, the creator of Truth, the very tool of love’ (p. 294). In the beginning was the end, and the arousal from the dream becomes recognition of the pearl, the black inked pearl. This is a novel that is to be enjoyed by all, particularly readers who derive pleasure in a specialized use of language to evoke mind-bending realism.

This book review was published in: Africa Book Link, Summer 2016