Afterlives (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2020). Abdulrazak Gurnah | A Review by Annachiara Raia

Long-listed for both the 2021 Orwell Prize for Political Fiction and the Walter Scott Prize, Afterlives is the tenth novel by Zanzibar-born Abdulrazak Gurnah, who was awarded the 2021 Nobel Prize in Literature. This award has been regarded as “a family win” for East African writers or, more broadly, for Gurnah’s many devoted readers worldwide. As Kenyan writer Yvonne Owuor puts it in an interview with Meg Arenberg, “Gurnah is like the favorite uncle who is rather shy; thus there is extra pride that he is finally being discovered.”[1]

Arenberg has also aptly pointed out, however, that the right award has been given for the wrong reason: “The Nobel Prize committee in Stockholm pigeonholed the complex and cosmopolitan work of the Zanzibar novelist in conventional East/West terms—terms he’s always rejected.”[2] In fact, in all the novels the author has written since the late 1980s, the conventional notions of “East vs. West” or “world literature writer” are ceded in favor of multiple and relational cartographies. A prime example of this is Paradise (1994), a novel detailing the caravan trade of Tanganyika before World War I, which “has been most acclaimed and discussed for its subtle but elegantly intertwined narrative of shifting maps”[3] (Vierke, forthcoming).

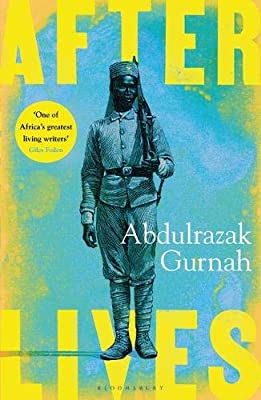

Clustered in four parts and comprising fifteen chapters, Afterlives leads the reader through “extended passages on the cruelties of the Kaiserreich inflicted in Deutsch-Ostafrika —which encompassed Tanganyika (now mainland Tanzania).”[4] The book cover depicts an Askari soldier of the German East African Schutztruppe in uniform, including a tarboosh with the Imperial Eagle badge.[5]

How Gurnah de-centers geopolitical maps and treaties and European historical accounts in Afterlives reveals one of the writer’s most exquisite talents: that of narrating the ordinary lives of people grappling with the haunting presence of colonialism and interconnected human woundedness, or, as Maaza Mengiste puts it, struggling with “what remains in the aftermath of so much devastation.” Therefore, one might ask, what does remain in such afterlives? In order to find out, the reader is led on a journey with Gurnah’s characters, their social struggles and passages of self-discoveries. As poignantly put by Mohineet Kaur Boparai, Gurnah “does what history does not, which is to reach into the recesses of lived experience.”[6]

Krieg. Vita. War. “Who are we fighting?”[7]

We collect fragments of what remained in the aftermath of the German occupation by following the stories of two veterans of the Schhutztruppe, Hamza and Ilyas, and their different yet entangled final destinations in life: the former in the town where he had lived as a child, the other in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp outside Berlin.

“At the very end of the war, when we were all exhausted and half-mad from the bloodletting and cruelty we had been steeped in for years,” Hamza is healed by Frau Pastor – as she is referred to in the book – and realizes how much they all risked their lives “for these vainglorious warmongers.” (Afterlives, 265). He strolls around different cities (Mwanza, Kampala, Nairobi, Mombasa) with no particular destination in mind, carrying with him nothing but two German books (Friedrich Schiller’s Musen-Almanach für das Jahr 1798 and Heinrich Heine’s Zur Geschichte der Religion und Philosophie in Deutschland). He eventually falls in love with and marries Afiya; they name their child Ilyas after Afiya’s brother, who was lost in the war.

From the beginning, the reader is immersed in typical Swahili biographical cartographies through the story of Khalifa and his father Qassim, who hailed from Gujurat but came to the Swahili coast of Africa on receiving an offer to join a bookkeeping team. Though Khalifa does not look Indian, his father married an African woman and always remained loyal to her: “Yes, yes, my father was an Indian. I don’t look it, hey?” (Afterlives, 3). Khalifa is the oldest character in the novel. His biography, retold via flashbacks, is entangled with historical events, bigger and smaller battles, as reflected in the following episodes.

When Khalifa begins studying mathematics, bookkeeping, and some basic English vocabulary with a private tutor, he is around eleven years old, exactly when “the Germans arrived in the town” and the al Bushiri revolt began (Afterlives, 5).

“The Germans and the British and the French and the Belgians and the Portuguese and the Italians and whoever else had already had their congress and drawn their maps and signed their treaties, so this resistance was neither here nor there. The revolt was suppressed by Colonel Wissmann and his newly formed schutztruppe” (Afterlives, 5).

By the time Khalifa is completing his period with the tutor, “the Germans were engaged in another war, this time with the Wahehe a long way in the south. They too were reluctant to accept German rule and proved more stubborn than al Bushiri, inflicting unexpectedly heavy casualties on the schutztruppe who responded with great determination and ruthlessness.” (Afterlives, 5).

During their baraza evening on Khalifa’s porch, we are introduced to the concerns of that time, “with rumors of the coming conflict with the British, which people were saying was going to be a big war, not like the small ones before against the Arabs and the Waswahili and the Wahehe and the Wanyamezi and the Wameru and all the others. Those were terrible enough but this is going to be a big war!” (Afterlives, 41).

“Uncle Ilyas is wounded at the Battle of Mahiwa in October 1917. (“I was there,” Hamza says. “It was a terrible battle.”)” (Afterlives, 274).

The character of Ilyas is introduced to the reader first as a “a friend of the manager, the great German lord himself. He speaks German as if it’s his native language” (Afterlives, 21). Through his conversations with Hamza, however, we hear more about his childhood: that he had to run away from home as a child, was kidnapped by a Shangaan Askari at the train station, and was eventually released and cared for by a German, after which he was sent to a German mission school, where—“don’t tell anyone”—he was made to pray like a Christian (Afterlives, 22). Mnafiki is thus what Hamza calls Ilyas, or “hypocrite,” an intertextual reference to sura 63 of the Quran, called Al-Munāfiqūn (“The Hypocrites”).

In one passage, we learn about Ilyas’s perspective on German kindness, which is met with hoots of laughter from the others, thinking there is no one as stern as a German: “Listen, just because one German has been kind to you does not change what has happened here over the years. […] In the thirty years or so they have occupied this land, the Germans have killed so many people that the country is littered with skulls and bones and the earth is soggy with blood. I am not exaggerating.” (Afterlives, 41). But Ilyas—of whom we lose track after he announces his plans to volunteer for the Schutztruppe—believes that his friend is in fact exaggerating.

Baba Khalifa, as a sensitive man who bears the burden of other people’s troubles and dies quietly at the age of 64, plays an intriguing role in the story; as the omniscient narrator witnesses him aptly say of Ilyas, “Maybe he had started to think of himself as a German or maybe he always wanted to be an askari. The reality was that he was always on the point of stumbling. You could not imagine someone more generous nor anyone more self-deluded than Ilyas.” (Afterlives, 199).

It is striking to see how only after the war does Hamza realize how the soldiers in the service of the German officer risked their lives “for these vainglorious warmongers.” (Afterlives, 265). During the war itself, the enthusiasm of being a soldier and fighting for the so-called governor of the Mdachi (“Germans”) resonates in this interpolated song:

It was not really a song, more like a sung conversation, delivered to a jaunty marching tempo with an explosive response at the end of every phrase (Afterlives, 52) :

Tumefanya fungo na Mjarumani, tayari. We have joined the Germans. We’re ready?

Tayari! We’re ready!

Askari wa balozi wa Mdachi, tayari. We are soldiers of the governors of the Mdachi

Tayari! We’re ready!

Tutampigania bila hofu. We will fight for him without fear.

Bila hofu! Without fear!

Tutawatisha adui wajue hofu. We will terrify our enemies and fill them with fear,

Wajue hofu! We’ll fill them with fear!

(Afterlives, 52)

The culture of brutality that the above excerpt illustrates is also reflected in several highly mimetic conversations, in which Swahili mingles with German, Arabic, and Bantu languages such as Kinyamwezi[8] and Kiswahili:

Unfahamu? [Do you understand?] Every order was shouted and accompanied by abuse. Ndio bwana. [Yes, sir.] (Afterlives, 60).

This is our Zivilisierungsmission. […] We have come here to civilise you. Unafahamu? [Do you understand?] (Afterlives, 65).

Among various other demeaning comments, we find “you are a bunch of washenzi,” (Afterlives, 51). where washenzi means “barbaric, indigenous from the mainland”;[9] “don’t swing your hips like a shoga,” (Afterlives, 51), where shoga refers to “very close female friends”;[10] and hataki mavi yenu ndani ya boma lake, “He doesn’t want your shit inside his camp.” (Afterlives, 54).

Swahili is mixed with German in the phrase haya schnell, when Hamza is ordered to lower his suruali (“trousers”) in front of the medical officer. (Afterlives, 57). The Arabic bil-askari (which means “like a proper soldier”) is highlighted as the exact mold in which the ombasha wants to train them. Specific threats also stand out vividly, such as “If it is not clean you will suffer kiboko na matusi in front of everyone, hamsa ishirin […] Twenty-five strokes of the cane on your fat buttocks.” (Afterlives, 58).

In fact, what remains in the aftermath of these entangled narratives are the many scars of “ignorance and narrowmindedness” (Afterlives, 105) and the overall culture of brutality that the writer recounts, happening in the so-called boma la mzungu (“the white man’s camp”) (Afterlives, 54) as well as in domestic contexts: a broken hand inflicted by an uncle in his own home as he believes that learning to write is wrong, or being slapped, ambiguously touched, injured, or accused of terrible misdeeds by the Feldwebel.

We see how “the brave little things” (Afterlives, 199) —like being able to write a note on a scrap of paper saying Kaniumiza. Nisaidie. (“He hurt me. Help me.”) or running off to war (Afterlives, 46, 199, 205–6) —enable one to drift somewhere else or rescue one’s own life. The novel indeed illustrates how the past is always at hand, and only time and love will be able to heal the scars and unite the wounded.

The scars after love

“So I don’t have any people to tell you about. I lost them when I was very young and I don’t know what I can tell you about … you want me to tell you about myself as if I have a complete story but all I have are fragments which are snagged by troubling gaps, things I would have asked about if I could, moments that ended too soon or were inconclusive.”

(Afterlives, 206)

In the last section of the book, the reader is immersed in the season of Ramadan, a period of fasting during which, in the novel, the scars will be recounted via the tender lovemaking and relationship between Afiya and Hamza. When Afiya slips into Hamza’s room, “whose door he had left ajar,” (Afterlives, 196) we hear more from both characters: “how brutal the culture was,” (Afterlives, 200) where the scar on Hamza’s hip comes from, and how he was healed by that “Frau Doktor” over more than two years in Kilemba.

Interestingly, the love story between the two characters starts with a piece of poetry that Hamza translates from German into Swahili, relying on the Musen-Almanach für das Jahr 1798 that the German officer had given him.

Hamza takes the first four lines of Schiller’s “Das Geheimnis” and translates them for Afiya:

Sie konnte mir kein Wörtchen sagen, Alijaribu kulisema neno moja, lakini hakuweza

Zu viele Lauscher waren wach, Kuna wasikilizi wengi karibu,

Den Blick nur durft ich schüchtern fragen, Lakini jicho langu la hofu limeona bila tafuti

Und wohl verstand ich, was er sprach. Lugha ghani jicho lake linasema.

Recurring cycles

The final chapters map out the war between the UK and Germany that has started in September. It is a period in which the administration has started publishing the Kiswahili monthly newspaper Mambo Leo, in which the people read all sorts of news, sport and health issues included, because “the government wants all of us to be healthy so that we can work harder”; (Afterlives, 225) the content provides a counterpoint to local healing rituals, such as the hakim visiting Afiya’s son Ilyas and helping him to “drink” the Quran through verses washed from a glided plate, (Afterlives, 252) or the shekiya ceremony with its scented candles, incense burners, and “perfume, drumming and stupid wailing,” as Hamza would describe such “nonsense.” (Afterlives, 255-57).

Despite Afiya’s superficial lack of interest in knowing what might have happened to the brother she lost, as if history can be conclusive—“What can we find out? […] What happened has happened” ((Afterlives, 202) —it is her son who, through German archival records, eventually traces Ilyas’s long journey to his death, which takes place in a concentration camp in 1942. His request to view the archives of the magazine and photo journal Kolonie und Heimat, stored in Koblenz, allow us to discover that Ilyas was marching with the Reichskolonialbund, a Nazi Party organization that wanted the colonies back, restored to Germany. To conclude, through Ilyas remarks “I knew nothing about a recolonizing movement,” (Afterlives, 271), we are duly invited to recall Giambattista Vico’s recurring cycles and reread how the Nazi Lebensraum did not only entail the Ukraine and Poland.

[1] BookRising. Yvonne Owuor on Abdulrazak Gurnah

[2] Latest from Meg Arenberg: https://newlinesmag.com/writers/meg-arenberg/

[3] Clarissa Vierke (forthcoming). “Zanzibari Worlds: A Relational Reading of Abdulrazak Gurnah’s By the Sea and Adam Shafi Adam’s Vuta n’kuvute.”

[4] Sean James Bosman (2021): Afterlives, Eastern African Literary and Cultural Studies, DOI: 10.1080/23277408.2021.1970872, p. 1.

[5] A picture of an Askari uniform, kept at the German Historical Museum, Berlin, can be found here: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2020/sep/30/afterlives-by-abdulrazak-gurnah-review-living-through-colonialism. Photograph: John MacDougall/AFP/Getty Images.

[6] Mohineet Kaur Boparai (2021). The Fiction of Abdulrazak Gurnah. Journeys through Subalternity and Agency. Cambridge Scholars Publishing, p. 2–3.

[8] Kinyamwezi is a Bantu language of western Tanzania. Being mother tongue of at least one million people, its main speaking-area is the town of Tabora. (Mganga, C. & Schadeberg, T. C. 1992. Kinyamwezi: Grammar, Texts, Vocabulary. Köln: Rüdiger Köppe.)

[9] Sacleux 1939: 602.

[10] Sacleux 1939: 843.

This review was published in Africa Book Link, Spring 2022