“…the future literary direction is…about the receded as it is about what is at hand”: A Review of The Gods Who Send Us Gifts: An Anthology of African Short Stories | by Nancy Henaku

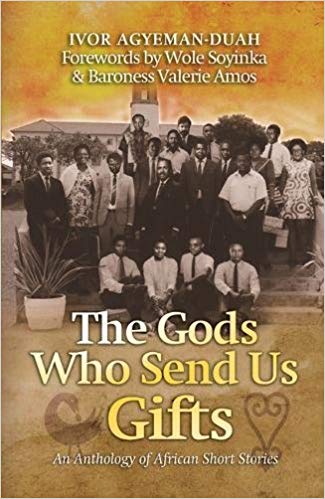

Last year (2017) was the fifty-fifth anniversary of the historic African Writers Conference held in June, 1962 at Makerere University in Kampala, Uganda. The conference which, as Obiajunwa Wali (1963: 14) rightly suggests “was faced with the fundamental question of defining African literature”, brought together many of the writers who will go on to influence African literature and criticism in significant ways. In celebration of this historic event and its central figures, Ayebia Clarke published The Gods Who Send Us Gifts: An Anthology of African Short Stories which, according to the collection’s editor, brings together “some of our most eloquent and able voices” who, through their stories, “pay their respects to those before them” (p. ix). The collection can therefore be considered as a celebration of Africa’s literary past and present as well as the continuities between them. This idea is, in fact, further reinforced by the cover of the collection which presents not only the iconic photograph of participants of the 1962 conference but also the Sankofa, an Akan Adinkra symbol that reinforces the need to look back at the past in order to pick for the present that which is good so as to forge for the future (see Kayper-Mensah, 1976). Here, it is significant to recall Agyeman-Duah’s explanation of the anthology’s title and justification for the choice of stories. The title is credited to the Ugandan writer Monica Arac de Nyeko who in an email exchange with Agyeman-Duah indicated: “The gods who send us stories, choose their own time” (p.4). This become an important basis for the envisioning of a fictional anthology with multiple themes. As an open collection, the anthology is characterized by a diversity of stories set in various parts of the continent. Through the diversity of its narratives, the collection provides us with a good blend of the old and new African literary flavor even as it points to the many uncertainties and possibilities about living in postcolonial Africa and in the process, raises critical questions about the politics of African literature itself.

Besides the seventeen short stories that make up its main section, the collection opens with three forewords written by Wole Soyinka, Baroness Valerie Amos and Pinkie Mekgwe respectively. There is also a prologue that features Kofi Awoonor’s poem “Those Gone Ahead” and finally, an introduction by Ivor Agyeman-Duah. I refer to these sections because of the ways in which they foreground the purpose of the collection and shape how readers engage with the short stories in the collection. In the first foreword, Wole Soyinka provides an insider’s perspective on both the 1962 and 1998 African Writers Conferences. Significantly, Soyinka’s narration seems to begin with a sense of nostalgia but ends with a sense of disillusionment that allows us to see the progression from what may be considered a more cultural African literary event (in 1962) to more political one (in 1998). Soyinka’s reflections provide behind-the-scenes details that allow readers to see in a new light those cultural pathfinders present at the 1962 conference. Of course, it was easy to imagine these rather romantic and enthusiastic young writers pontificating about African literature into the dead of night. It was, however, unexpected (and humorous too) to read about the quintessential Christopher Okigbo and his insistence on bringing a bargirl he nicknamed “The Muse of the Makerere Conference” to serve as hostess even as he ensured that “no one got fresh with her” (p. xvi).

Through Soyinka’s narration, we also learn details of the literary as well as the socio-political situation of 1960s Africa. For instance, we learn of the tensions in the Congo after the death of Patrice Lumumba and how the Nigerian delegation had a little fracas with a Congolese soldier who roughly pushed Frances Ademola for apparently not obeying his orders. It was insightful to learn that Wole Soyinka, J. P. Clarke and Okigbo “got physical” (p. xv) because as Soyinka suggests “you don’t just shove a member of the Nigerian delegation, and a woman at that!” (p. xiv). These minor details may seem insignificant; however, by the time one reads Soyinka’s reflection on his experience in 1998 at a museum memorializing the Rwandan genocide and his subsequent decision not to return to Kampala in search of the historic office of Transition, one begins to see the connections he has been drawing all along between morality (or a respect for humanity) and the role of the literary arts. The melancholic closing of Soyinka’s foreword somewhat causes us to wonder: what good is the literary arts in the face of overwhelming evil? Interestingly, the connection between politics and literature seems to be a central theme within the collection and this is confirmed by Mekgwe who, in the third foreword, suggests that the stories are “a basis for questioning cultural values that impede progress” and that “there is a need as well for preservation of literary history and the efforts of the elders” (p. xxv). In this sense then this collection could be considered as mainly “political” and perhaps fits into what may be considered as an instrumentalist view of the function of African literature.

Significantly, Soyinka’s recollection could be juxtaposed with Sefi Atta’s short story “The Conference” which gives a contemporary twist to long-standing debates on the politics of African literature. Through humorous and animated dialogue between characters, Atta zooms in on the complex politics surrounding the state of contemporary African literature. The story, which is set in an African Literature Association conference in Illinois, foregrounds the conversations and actions of two central characters, the firebrand Ranti, who is an associate professor of African literature in the United States, and the more ambivalent narrator, who has only recently moved to the United States and is in search of an academic position after a stint in the banking world. Through Atta’s narrative, readers begin to see the differences between the politics underlying the 1962 Makerere conference and the fictional conference presented in the short story. Most significantly, by setting Ranti and the narrator as foils to each other, Atta exposes readers to the varied perspectives on the issues under discussion and leaves room for reader’s personal judgement. Among other issues, the story brings to the fore the ironic implications of convening an African literature conference in the West rather than continental Africa as was the case for the 1962 conference and significantly, through the words of Professor Imana, one of the characters who is vehemently challenged by Ranti in the course of the narrative, readers are asked to ponder this state of affairs. As she says: …remember the standard that was set at the conference at Makerere University in 1962…Now here we are today, in 2000, holding an African literature conference in Illinois. Ask yourself why. Give that your time and consideration (p. 20).

Sefi Atta’s narrative further highlights the politics of geopolitical and linguistic representation at the fictional conference, an issue that has been the subject of critique even for the historic Makerere conference (see Wali, 1963; wa Thiong’o, 1986). It was therefore surprising to notice the absence of stories in African languages within the collection especially when other more recent collections like the New Orleans Review’s African Literary Hustle featured some stories in African languages. Another issue that seem central to Atta’s narrative is globalization and more specifically, the politics of international literary awards and their implications for African literary production and consumption. Here, the discussions between the characters about an award received by one Osaro was insightful as it reminds readers of critiques of the complex global factors framing African literary awards and how these ultimately result in what some have considered as the “aesthetics of suffering” (see Habila, 2013) in African literature. In relation to the issue of globalization, the short story causes us to reconsider the politics of defining and categorizing African literature. For instance, through narratorial commentary, Atta shows how writers like Gordimer and Coetzee are sometimes eliminated from the category African literature because they are sometimes classified as world literature. Critical questions are also raised about the fraught relations between scholars and producers of African literature, the question of African feminism and its representation in literature as well as the differing readings of African literature on the continent and outside the continent.

Besides the obvious discussions on African literary conferences, the anthology explores the connections between politics and African literature through its many other themes. Here, Ama Ata Aidoo’s “Gravisearch”, the first story in the collection, is especially significant. As a story written by an older African writer, “Gravisearch” reminds us of the explicit ideological underpinnings of earlier African literary writing. Narrated by a postgraduate student researching The Origins of Ghanaian Flora and Fauna, this story has as its main themes the politics of food, the politics of naming and the politics of knowledge production as evident in the excerpts below:

I was very happy with my research, although quite a lot of the stuff I came across was rather cruel, scary or just plain nasty. But as everyone knows, in research as in life, sometimes the journey is the thing; and I was extremely happy.

Until one day. You know what I discovered? You won’t believe it…I was on the internet chasing after ‘aboboe’, aka bambara beans, aka Congo goobers aka ‘gurjiya’ aka ‘okpa’ and literally hundreds of other names by which it is known across Africa, when I came upon some research paper produced in a U.S university in which they claimed that unlike the bambara bean, the peanut was imported to Africa from the United States of America…How about all those people aboard those truly wretched schooners, chained, whipped, starved, who against all odds, had hid the peanut in unmentionable parts of their anatomies throughout the horrors of the Atlantic Crossing, I kept asking myself.

That’s how come I lost my happiness (p. 8).

As with many of Aidoo’s narratives, the story interrogates coloniality of power in its varied forms. Here, she draws connections between her main themes and issues related to colonialism, slavery, transnationalism, gender– ideas that have been central in Aidoo’s previous works. Indeed, “Gravisearch” shares many of the characteristics of Aidoo’s narratives including the foregrounding of female characters as well as representations of the grandmother as a repository of knowledge. In “Gravisearch”, it is the grandmother’s explanation of naming practices for Ghanaian flora and fauna that ultimately informs the narrator’s future research. In many ways, Aidoo’s narrative is steeped in the past, through its connection with her earlier works, but it also engages with the present in two significant ways. First, though a brief portion of the story, the narrator’s engagement with the internet as a political tool reminds us of new aesthetic forms defining contemporary African literature. Here, Ifemelu’s blogging as a way of writing back at the center in Adichie’s Americanah comes to mind. Moreover, by ending the narrative with a recipe which the narrator publishes online, Aidoo’s work further contributes to ongoing interests in food writing in African literature although, this is, in fact, not the first time Aidoo has written about food politics (see for example the short story “Nutty” in Aidoo’s The Girl who Can and Other Stories).

Other themes explored in the collection include sexual abuse (as in Ogochukwu Promise’s “What Could the Matter Be”), the complications of transnational relationships (as in Ivor Agyeman-Duah’s “”The Good Ones”), intrigues of succession politics (as in Boubacar Boris Diop’s “Goodnight Prince Koroma), the violence of war (as in Zukiswa Wanner’s “Upon this Handful of Soil), institutional corruption (as in Maliya Mzyece Sililo’s “Damn the Receipt”) and so on. One significant aspect of many of the narratives is how they highlight the precarity of living in post-colonial African societies. Many of these narratives are characterised by violence in its myriad forms. For instance, Diop’s “Goodnight Prince Koroma” ends with the assassination of a prince by a government official and Richard Ali A. Mutu’s “A Labour of Love and Hate” presents a rather bizarre narrative involving killings and sexual violence. While Ivor Agyeman-Duah’s narrative centres on the complexities of transnational relationships, a significant section of the narrative zooms in on the reaction of the protagonist to the horrors of the Rwandan genocide once again reminding us of Soyinka’s reflection in his foreword. Rwanda seems to feature in quite a number of the narratives. Njabulo S. Ndebele “Death of a Son’ points to the violence of soldiers and police in a South African township and how this led to the killing of the son of a reporter. However, to reduce the narratives to a certain emphasis on precarity alone is to ignore the many complex emotions that run through the stories and what these suggest about the spirit of survivance that underscores the dynamism of life in African contexts. For instance, while “Death of a Son” gives insights into institutional brutality under apartheid South Africa, the narrative is also very much about the ways in which the main character and her husband Buntu deal with the tragedy that befalls them. Melancholia and desperation are obviously the dominant emotions in this narrative; however, these emotions are presented with a kind of literary subtlety so that in the end, readers come to appreciate that even in the face of such tragedy, there is a possibility “to be free to fear” (p. 121).

In spite of the centrality of violence in many of the stories, not all of them are about tragedy. Some like Mary Ashun’s “African Connection”, Bwesigye Bwa Mwesigire “In the House of Mitego” , Maliya Mzyece Sililo’s “Damn the Receipt”, Louise Umutoni’s “The Proposal” and Mukuka Chipanta “The Lady, the Dreamer and the Blesser” provide a different view into life in African contexts. In fact, Mary Ashun’s narrative is, for instance, not about violence at all but about the stress that comes with her position as the Vice Principal of a small International School in Accra. When the story begins, the narrator seems to be enjoying what she calls her “sanity day” so as to “rejuvenate those brain cells that have died in the course of the school term” (p. 104). In a flashback, the narrator foregrounds the stress that comes with her work by recounting the actions of one “been-to” mother who seem to have a problem with the school’s shift from paper to electronic report cards. Like the other narratives, this story also has a political twist as it highlights a struggle for power between school authorities and a parent (evident in the discourse of the emails exchanged between the narrator and the principal of her school). The story is also a critique of the actions of a supposed “been-to” who as the narrator suggests is one of those people who, “after several years of being treated like second class citizens in another country…”, think “they have the God-given right to abuse those amazingly good things that are happening in Africa” (p. 108). In Maliya Mzyece Sililo’s “Damn the Receipt”, readers see the frustrations of a grandmother who refuses to do ‘the right thing” (that is pay bribe) when she is initially stopped by the police. This story too contains some violence but this remains marginal to the overall narrative and for many African readers, some aspects of the narrative may be hilarious. Told from the perspective of a young boy who lives in a barracks, Bwesigye Bwa Mwesigire “In the House of Mitego” draws attention to police brutality through the main character’s actions with his friends at playtime but the narrative is perhaps more about the child’s relationship with his disciplinarian mother and the absence of his father. Beyond this, the stylistic features of Mwesigire’s story draws attention to the question of language in African literature. By mixing indigenous linguistic expressions like “kanayfu”, “kibuunu”, “kapere” with English, Mwesigire creates what Zabus (2007) have called a palimpsest because “behind the scriptural authority of the European language, the earlier, imperfectly erased remnants of the African language can still be perceived” (p. 3). Depending on the reader, this stylistic move could be considered decolonial as Mwesigire’s linguistic choices, like those of earlier African writers, causes the English superstrate to bear cultural imprints of an African language.

Finally, most of the narratives explore the intricacies of human relations. There are stories like Louise Umutoni’s “The Proposal” that explore human relations through love but there are also those like Mary Ashun’s “African Connection” that explores this themes mainly through conflicts. Agyeman-Duah’s narrative is as much about the love between the protagonist and her boyfriend as it is about the relations between the protagonist and her mother. Ntasano’s “Recipe for an Escape” shows us the fraught relation between a father and a supposed homosexual son, Seki, whose way of life, we are told, challenged “the integrity and moral fabric of his family and Burundian society” (p. 136). Seki’s ultimate purpose was to prove to his father that he was “worthy” but while still in exile, his father died and this singular event will affect this good-natured chef, who though had never shed a tear in spite of all the experiences he had gone through, “let out a tear” because as the narrator suggests “things have come full circle…all roads lead to the past” (p. 140). This emphasis is also evident in Wame Molefhe’s feminist piece “A Woman is Her Hands” which shows the intergenerational relations between the protagonist, her mother and grandmother and her ultimate suggestion that “…when you have a daughter of your own, she will not become you or your mother or your mother’s mother…You’ll make sure that she become more than her hands” (p. 182). This aspect of many of the narratives evokes all kinds of pathos. This is, for instance, evident in the melancholic tune that the narrator of Monica Arac de Nyeko’s “Grasshopper’s Redness” hear in her grandfather’s humming or when her mother sings:

Water has taken

Water has taken

My friend

Water has taken

Water has taken

My friend (p. 150)

In one of the forewords, Pinkie Mekgwe suggests that “the future literary direction is…about the receded as it is about what is at hand” (p. xxv). This is evident in the many African stories featured in The Gods Who Send Us Gifts. Together, these stories remind us of where African literature has been before, where is it is at present, where it might be going in future. But by focusing fundamentally on the connection between politics and literature, the collection also poses an important question: what should African literature do? Here, we are reminded of earlier debates about the function of African literature. Significantly, many of the narratives underscore the uncertainties of living in contemporary Africa. While precarity is obviously a dominant motif in this collection, the authorial voices behind the various stories seem too self-conscious to perform an “aesthetic of suffering” for the West. This collection is, in many ways, a literary revisioning of a better Africa and this is perhaps a reason for its emphasis on varied relations whether between lovers, parents and children, school authorities and parents, state institutions and citizens etc. Perhaps this should not come as a surprise because all narratives are deeply relational and for a text that’s deeply invested in forging a new society, this element in The Gods Who Send Us Gifts allows readers to see themselves anew.

References

Agyeman-Duah, Ivor. (2017). The Gods Who Send Us Gifts: An Anthology of African Short

Stories. Oxfordshire: Ayebia Clarke

Habila, Helon (2013, June 30). “We Need New Names by NoViolet Bulawayo – Review.” The

Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/books/2013/jun/20/need-new-names-bulawayo-review

Kayper-Mensah, A. W. (1976). Sankofa: Adinkra Poems. Ghana Publishing Corporation

Wali, Obiajunwa. (1963). The Dead End of African Literature? Transition, (10), 13-15

Wa Thiong’o, Ngugi. (1986). Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African

Literature. Nairobi: East African Publishers

Zabus, C. J. (2007). The African palimpsest: Indigenization of Language in the West African

Europhone Novel. Amsterdam: Rodopi

Nancy Henaku (PhD Candidate /Graduate Teaching Instructor Rhetoric, Theory and Culture, Michigan Technological University)

This book review was published in: Africa Book Link, Summer 2018