Interview with Noo Saro-Wiwa on her recent memoir Looking for Transwonderland | by Elizabeth Olaoye

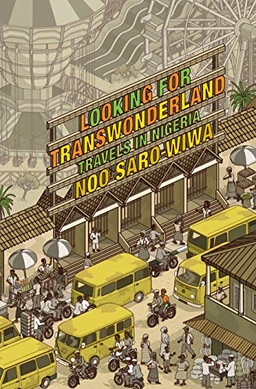

Noo Saro Wiwa is a Nigerian- British Travel writer who Condé Nast Traveler Magazine listed as one of the 30 most influential women travelers. She was born in Port Harcourt, Nigeria, and raised in England, where she attended King’s College London and then Colombia University in New York. She has contributed book reviews, travel, opinion, and analysis articles for The Guardian newspaper, The Financial Times, The Times Literary Supplement, City AM, Chatham House, and The New York Times, among others. Although her genre is non-fiction, the keenness of her vision and her ability to look at ordinary everyday realities with an artistic vision makes her travel memoir, Looking for Tanswonderland: Travels in Nigeria, a great reference point in the discussion of narratives set in Lagos, Nigeria’s commercial capital. I discovered this memoir while writing my dissertation on the gendered portrayal of Lagos in contemporary narratives and find it fascinating. I asked if Noo would answer some questions on the text, and she agreed. I’m excited to share some of her responses here:

To what extent is Looking for Transwonderland a non-fictional work? Are there fictional elements in the narrative? If yes, can you give examples?

The book is 100% non-fictional. I take great pride in reporting my experiences faithfully. Real life is more interesting than fiction, especially in places like Nigeria. The only times I tweak names or details is to protect someone’s privacy, particularly for safety reasons.

Did you have to change names to conceal identities?

Yes, see above.

I know you write travel narratives. Have you tried or considered fiction?

I’ve considered it, but I find it much harder than non-fiction. Maybe one day.

The idea of a Transwonderland is fascinating, especially considering the linguistic possibilities in the word. Moreso, an amusement park in Ibadan has a name close to that. What exactly did you mean by transwonderland?

Transwonderland is the name of the dilapidated amusement park in Ibadan. My book title is a metaphor for my search for that touristy side of Nigeria, which I wanted to explore as a way of disassociating from the painful memories of my father’s death at the hands of the military regime. But I found that the touristy side, such as Transwonderland amusement park, was often rundown: neglected natural reserves and safari parks, etc.

The memoir says that, “being Nigerian can be the most embarrassing of burdens.” This statement is about Nigerian travelers’ cacophony at Gatwick Airport. Can you discuss this further? How often do you experience this burden? Is it physical or psychological? Has this something to do with the physical location or the attitude of the people?

Nigerians are constantly embarrassed by the failures of our government. Our diaspora contains some of the most successful immigrant groups in countries like the United States. We have so many smart, talented people, yet as a nation Nigeria is not worth the sum of its parts. Decades of poor governance has led to poverty, a lack of education, an increase in criminality, and a mistrust of authority (the latter demonstrated by that cacophony at Gatwick airport). Unfortunately, that’s the image of Nigeria in the eyes of the world. When you tell people you’re Nigerian you can often see the hidden disdain, or at least lack of admiration, in people’s eyes.

I noticed that the extreme religiosity of Nigerians repeatedly features in your memoir. Do you see this as a kind of agency for Lagos’s powerless people or a manifestation of sanctimony ecstasy?

The extreme religiosity is a result of economic failure caused by perennial corruption and structural adjustment policies in the 1980s. Nigerians began to import the ‘prosperity gospel’ from the United States (white Americans invented it) as a coping mechanism. Every society, be it in Europe, the Americas or Asia, responds to poverty in its own way in order to survive financially and psychologically.

Do you think it’s paradoxical that you refer to yourself as a tourist in your own country?

No, tourists can be domestic or foreign. I would say most people haven’t seen the beauty spots in their own countries, which is a shame.

Would you travel to Lagos again? Why or why not?

I touch base with Lagos at least once every two years as I have friends and family there.

What do you detest most about Lagos?

It’s too noisy. Constant music everywhere you go; you can’t escape it. There are almost no public spaces to enjoy quiet contemplation or meditation.

What do you love most about the city?

Like all major cities, it’s big and full of energy. There’s lots going on, always new developments (architecturally, culturally, etc.). Things are always changing.

Taiye Selasi describes Afroplolitans as Africans of the world. Recently, scholars have been knocking heads on the privileged position that tempers Afropolitan narratives. A travel writer fits that description. Do you view yourself as an Afropolitan?

If the definition of an Afropolitan is an African who owns a passport and does a job that enables them to travel easily to other countries, then yes I’m an Afropolitan. There aren’t many such people. Having a British passport puts me in a very privileged position, and I never taken it for granted. I know the struggles that Nigerian passport holders have. It affects their ability to work, study or simply explore different parts of the world.

Are there potentials in Lagos that are not being harnessed right now?

Yes. Every human being has potential, and if the government is not investing in them (through education) then their potential is not being fulfilled. In Lagos – and Nigeria as a whole – there are millions of potential entrepreneurs, astronauts, teachers, lawyers, journalists. But instead they are living parallel lives as impoverished, struggling citizens.

Do you think that the spatial structures of the city (Lagos) are not neutral? Do you think it would have been easier to navigate the city as a man? How does Lagos treat women?

To be honest, it’s hard to answer this question as I don’t live there. I find Lagos easy to navigate as a short-term visitor with dollars in her pocket and an Uber app on her phone. Living there, however, is another matter.

Have you visited any other place that created the same feelings that you had in Lagos? Did any other city present similar precarious situations?

Lagos is pretty unique. I’ve been to massive cities like Manila and Cairo, but their infrastructure always seems slightly better than Lagos. But maybe that’s only because I haven’t seen their poorest areas.

What do you think about the presence of the supernatural in the African psyche as manifested in our movies and literature?

It’s important that literature and movies reflect our psyche – it’s what makes it authentic. The supernatural can be confusing and inaccessible to non-African audiences when production values are poor, but when such themes are explored by talented artists like Akwaeke Emezi, Wole Soyinka or Nnedi Okarafor it’s great.

Elizabeth Olaoye

Idaho State University