Achebe and Friends at Umuahia: The Making of a Literary Elite – Terri Ochiagha | A Review by Sola Adeyemi

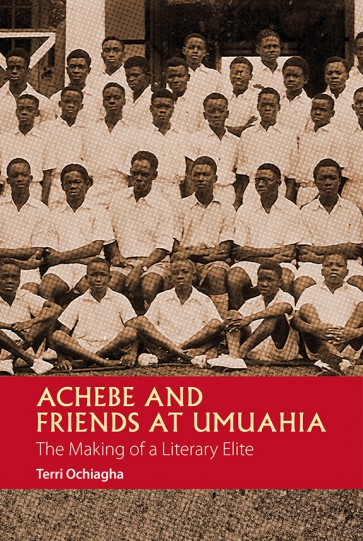

Known by several names in its nearly a century as a centre of building character and developing intellect, including Primus Inter Pares among all Government Colleges in Nigeria and ‘The Eton of the East’, Government College Umuahia (GCU) has been one of the more important secondary schools in Nigeria. Founded as a teacher training institution in 1929 on a ‘desecrated’ land, with twenty three eager male students, the status was changed a year later to that of a boarding secondary school with the remit to produce competent men to work in the general administrative and teaching sectors of the colonial government. Government College Umuahia later became THE SCHOOL which has not only produced many important figures in the history of Nigeria, but has been the womb of creation of major Nigerian literature. Indeed, as Terri Ochiagha establishes in her new book, Achebe and Friends at Umuahia: the Making of a Literary Elite, Government College Umuahia has been influential in the literary and political development of Nigeria. A labour of love, Ochiagha conceived and wrote this book to, as she puts it, ‘unravel the literary mysteries of my youth’, an unravelling that has become an important contribution to the scholarship in African literature.

Achebe and Friends at Umuahia is a major study, the first to examine the importance of GCU in the nurturing and development of some of the major writers in Nigeria. The writers particularly mentioned in the book include Chinua Achebe, Chukwuemeka Ike (Toads for Supper and Expo ’77, the first Nigerian detective novel), Chike Momah (Friends and Dreams), Christopher Okigbo (Heavensgate) and Elechi Amadi (The Concubine). Ochiagha also looks briefly at the effect of the GCU tradition on Ken Saro-Wiwa, who was executed by the Nigeria government in 1995, and I.N.C. Aniebo, both writers who infused local speech patterns and sensibilities into their works.

Divided into eight chapters, this monograph provides an insight into the culture and tradition that formed these young men in the early 1940s and turned them into lifelong friends and collaborators with unified aims of making enduring changes in the postcolony. Perhaps the most exciting format of the book lies in the structure, which, rather than being chronological as you would expect of a historiography, or thematically subdivided, is set out in a circular structure with interweaving subjects and striking pointers that cross reference one another. The book begins with an introduction to the ‘Umuahian writers’ before giving and overview of the first few years of GCU as a teacher training and secondary school that provided education ‘along the African’s own lives’, a philosophy that the founding principal Robert Fisher, strictly adhered until the period of Second World War when the school became a billeting space for the colonial army as well as a concentration camp of some sort to German prisoners of war from the Cameroons.

Chapter one discusses the ideological tensions underlying the school’s adaptation of the English public school model and the vocational principles of Dauntsey’s School in Wiltshire, England. Ochiagha stresses in this chapter the influence of religion and culture in the experiment that the founding principal, Robert Fisher, ‘conducted’ in the formative years. The second chapter traces the transformation of this ‘cultural’ school into a bona-fide English public school under the principalship of William Simpson, and the ideological and educational consequences of this revolution. This second chapter is perhaps the most important, as it establishes the ethos of the school as it sets the standard for educational and sporting credentials that later underpins the fame of the school. Simpson ‘tried to establish the very best in the English public school tradition’ (p.49), with a regimented schedule of activities supported by ‘reward and sanctions’ for accomplishments in the area of intellectual and character development. The competence of the teaching staff, made up of Nigerians and British Commonwealth citizens from as far afield as Australia also contributed to growth of this tradition, especially in cricket and other sports. Chapter three is devoted to the introduction of these teachers and their efforts in getting the students to achieve the best results in the Cambridge School Leaving Examinations.

Chapter four expands the study to embrace the nationalist fervour that emerged after the Second World War and the relevance of the campaigns by activists and politicians such as Nnamdi Azikiwe, the first President of the independent Nigeria, in shaping and informing the political awareness of the students. Ochiagha here mentions that this influence did not go unchallenged or unremarked in the school, as the authorities tried to ‘rein in and re-direct the impact of anti-colonial ideas’ (p. 15). After all, GCU was still a government funded school with a curriculum designed by government officials to produce middle class workers for the colony. Chapter five examines students’ writings that responded to the ‘censuring’ by the school authorities and ‘new knowledge’ by the nationalists, with a reproduction of two significant pieces of writing – Chukwuemeka Ike’s short story, ‘In Dreamland’, and Elechi Amadi’s poem, ‘A Social Day with the C.C.C.’ This chapter also highlights the training these writers had by functioning in the position of authority in the universe of the school; for instance Achebe was the Editor of the Niger House journal, The Excelsior in 1947, a position he also held on the University Herald at the University College, Ibadan in 1951-52; Chukwuemeka Ike and Christopher Okigbo were editors of The Athena, the journal of the School House in 1949-50.

Ochiagha expanded the focus of the monograph in chapter six by using the template of interculturalism, especially Homi Bhabha’s idea of colonial mimicry and the third, liminal space, to review some of the writers’ constructs that interrogated the complexities of identity creation and probe the struggles present at the crossroads of cultural interaction. Here, the author controversially tries to link the education at Umuahia with the idea of colonial indoctrination, exposing dim connections between the perceived intentions of the writings of Ike, Okigbo and Momah, among others. Whilst not totally successful, the attempt raises valid questions about the nature of colonial education and lasting effect on the intellectual development and productivity of the men. The final chapter – chapter eight – further elucidates the ‘convergences and divergences’ in the poetic and literary practice of the five major writers whose works are referenced in this boom – Achebe, Amadi, Ike, Okigbo and Momah. Okigbo is especially mentioned as trying to reimagine the ‘primus inter pares’ years of GCU in the use of sporting (cricket) imagery in his poems. It concludes by singling out – and this is quite remarkable for its intertextuality – a distinctive ‘Umuahian’ ethos in their work and proffering a reason for the affinity and thematic closeness in the works, stating that this is derivative of the nature of the education provided by GCU in the 1940s and 1950s. Achebe and Friends at Umuahia ends with the funeral of Chinua Achebe in 2013 and the moving performance of the school anthem by a group of old students and friends of Achebe. It links the literary lives of the five major writers and pointing at the unstoppable final ‘departure’ of these men whose incursion into the literary live of Nigeria remains enduring.

The seventh chapter, which examines the writing of Ken Saro-Wiwa and I.N.C. Aniebo, serves as the ‘control’, a placebo attempt to check for changes in the Umuahian experiment of the 1940s. However, it reads like an ‘orphan’ chapter that does not fully blends in with the rest of the book; it should have been excised as a separate study and the monograph would not be poorer for that reason.

There are a few repetitions in the book, such as Achebe’s ‘they weren’t teaching us African literature. If we had relied on them to teach us how to become Africans we would never have got started…’ but these could be attributed to the ‘circular structure’ of the book. However, proofreading of the final manuscript was not as stringent as you would expect of such an important, ground breaking book (see the last line of page 48, for example, where ‘education’ is written as ‘rducation’). Nevertheless, this book is a new perspective on British colonial education in Nigeria and the development of Nigeria’s modern literature, especially in the way the writers’ visions were shaped to re-inscribe African literature. There are, in addition to the plethora of information in the book, an appendix of bibliographical materials of the five major writers, including a list of supplementary online material and sources.

This book review was published in: Africa Book Link, Summer 2015